|

Clinical Cases |

|

Atherosclerosis is a disease process that falls under the broader category of arteriosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis is a general term that refers to any hardening (-sclerosis) of the arteries (arterio-). Three disease processes fall under the heading of arteriosclerosis:

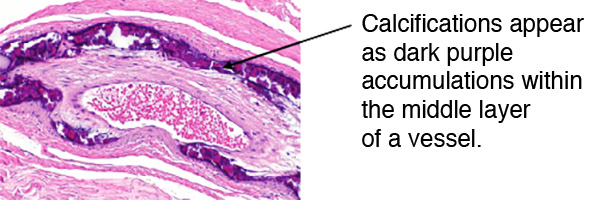

- Monckeberg's medial calcific sclerosis - A benign type of dystrophic calcification in the tunica media of arteries. Has no effect on lumen size and so is of little clinical importance.

Image obtained from Creative Commons.

- Arteriolosclerosis - Hardening of the arterioles. Two types:

- Hyaline arteriolosclerosis - Characterized by major hyaline deposits in the tunica media that results in both hardening of the arteriole and decreased lumen size. Most typically occurs in the kidney as a result of hypertension and diabetes.

Image obtained from Creative Commons.

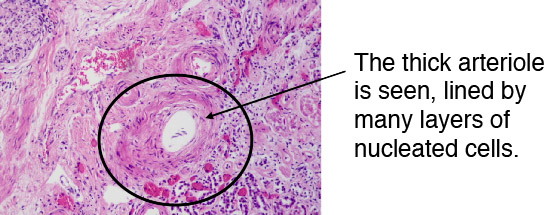

- Hyperplastic arteriolosclerosis - Proliferation of arteriole media, resulting in severe reduction of lumen. This disease process is most often seen in the kidney and is the hallmark of severe hypertension (BP~ 250/140).

Image obtained from Creative Commons.

- Atherosclerosis (etymology: athero-, meaning gruel or mush-like. -sclero, meaning hard. Atherosclerosis= hardened mush) - Atherosclerosis is by far the most clinically significant form of arteriosclerosis. It is a disease of large and medium sized arteries (typically those arteries that have names in gross anatomy), and is very often visible in cadavers on dissection and CT visualization.

Pathogenesis

The healthy arterial wall consists of 3 layers: a thin tunica intima consisting of endothelial cells, a thick tunica media composed of internal and external elastic laminae and smooth muscle cells, and the tunica adventitia composed of dense, irregular connective tissue and vasa vasorum (small blood vessels supplying muscles of the arterial wall).

Image obtained from Creative Commons.

The development of atherosclerotic lesions is thought to be a response to endothelial damage and dysfunction. Lesions begin as fatty streaks that result from the accumulation of cells (macrophages, lymphocytes, and smooth muscle cells) in the tunica intima, and the accumulation of lipid and cellular debris as these cells undergo necrosis.

Image obtained from Creative Commons.

Image obtained from Creative Commons.

Most fatty streaks remain benign, but those that progress go on to become atheromas. As smooth muscle cells continue to proliferate and more foamy macrophages (full of lipid) accumulate, the atheroma develops a core consisting of fatty tissue and necrotic cellular debris. Fibroblasts lay down collagen and other extracellular matrix constituents to form a fibrous tissue envelope around the atheroma. Cholesterol clefts form in the now enlarged intima as necrotic cells liberate more and more lipid. Dystrophic calcification occurs as an attempt to contain the lesion.

Image obtained from Creative Commons.

The sequelae of these patchy, multifocal lesions in the major arteries are numerous and diverse in consequence. These lesions can remain silent, never causing the patient harm. They can also gradually diminish the flow of blood through the artery as the lesion grows and slowly begins to occlude the lumen.

If the fibrous roof of the lesion gives way, the lesion can thrombose, potentially leading to an atheroembolism.

Image obtained from Creative Commons.

The presence of vaso vasorum in the adventitia of major arteries increases the risk of hemorrhage into the lesion, which can lead to an acute occlusion of the artery lumen as the hemorrhage swells and raises the roof of the lesion into the lumen.

Atherosclerosis can also cause weakening of the arterial wall, increasing the risk of aneurysm and arterial rupture.

Image obtained from Creative Commons.