|

Clinical Cases |

|

Cholelithiasis

Choleliths (gallstones) are crystalline bodies that form in the biliary tree when bile components aggregate and undergo concretion. Stones can occur anywhere in the biliary tree. When a stone forms in the gallbladder, it is called cholecystolithiasis. When a stone forms in the common bile duct, it is called choledocholithiasis.

Stones vary in size from grainy, sludge-like bile to golf ball sized calculi, and can occur as a single large stone or multiple stones. There are two types of cholelith based on content:

- Cholesterol stones: These are green, white, or yellow stones that are made mostly (70-80%) of cholesterol, with calcium salts and bilirubin compounds making up the other 20-30%. These occur because the bile contains too much cholesterol and not enough bile salts. Other contributing factors include inefficient and infrequent gallbladder contractions, which allow bile to sit in the gallbladder for long periods of time, resulting in an over concentrated bile that is conducive to stone formation. No clear link between diet and risk for cholelithiasis has been shown, though it has been suggested that diets high in cholesterol and low in fiber may increase one's risk. A mnemonic for remembering risk factors for cholesterol gallstones is the 5 F's: Fat (overweight), Forty (age near or above 40), female, fertile (premenopausal- increased estrogen is thought to increase cholesterol levels in bile and decrease gallbladder contractions), and fair (gallstones more common in Caucasians).

Cholesterol Gallstones

- Pigment stones: Dark stones, usually small, that contain less than 20% cholesterol and are composed mainly of bilirubin and calcium salts. Risk factors include those disorders that result in excessive bilirubin production, such as hemolytic anemia (when hemoglobin is liberated from red blood cells it is broken down and its heme component is eventually degraded into bilirubin by the liver, which then uses the bilirubin in bile). Other risk factors are cirrhosis and biliary tract infections.

Pigment GallstonesConsequences of Cholelithiasis

Numerous clinical consequences and pathologies arise from cholelithiasis. Here are some of the major consequences and treatment options:

- Cholecystitis - This term means inflammation of the gallbladder, and it is most commonly caused by choleliths, though an acalculous (without gallstones) form can occur in debilitated and trauma patients. Typically a gallstone will form in the gallbladder and move into the cystic duct where it occludes the lumen and prevents bile from exiting the gallbladder. This leads to thickening of the bile, bile stasis, and secondary infection by gut organisms such as E. coli and Bacteroides species. The gallbladder lining consequently becomes inflamed, potentially progressing to irritation of the surrounding tissue (bowel, diaphragm), necrosis, or rupture. Cholecystoliths can cause either acute attacks or chronic, low-level inflammation that results in a fibrotic and calcified gallbladder.

- A less common but clinically interesting scenario is when the gallbladder becomes inflamed and adheres to a section of bowel. If the gallbladder ruptures it can form a fistula with a section of bowel, which allows choleliths to pass into the bowel resulting in a gallstone ileus (see beginning of Dr. Ramsburgh Histopathology lecture Neoplasia II).

- Though non-invasive therapies do exist, definitive treatment for cholecystitis is cholecystectomy (surgical removal of gallbladder).

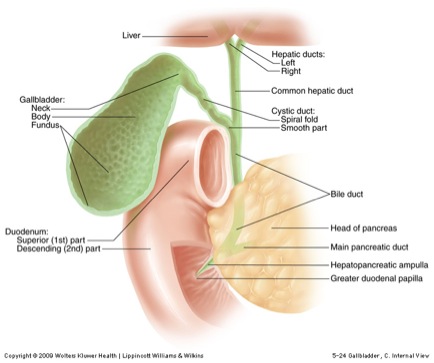

- Choledocholithiasis - The presence of gallstones in the common bile duct is a medical emergency because it impedes the flow of bile from the liver to the duodenum, resulting in jaundice and liver cell damage subsequent to increased alkaline phsophatase, conjugated bilirubin, and cholesterol in the blood (as bile backs up into the liver, bile products and liver enzymes begin rising in the blood). Diagnosis is dependent first on diagnosing cholelithiasis (if no stones are present, stones can't be blocking the common bile duct). Often a procedure called ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) is done to both confirm the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis and provide treatment. This procedure involves passing an endoscopic orally into the duodenum where the hepatopancreatic ampulla (ampulla of Vater) opens to the main pancreatic and bile ducts. If a stone is seen obstructing the biliary tree, it can sometimes be removed by the endoscope as it widens the duct lumen, allowing the stone to be passed into the duodenum.

- Pancreatitis - The most common cause of acute pancreatitis is gallstones (alcohol is the most common cause of chronic pancreatitis). Gallstones cause pancreatitis when they pass out of the gallbladder, down the common bile duct, and become lodged so as to obstruct the outflow of the pancreatic exocrine system at the main pancreatic duct. ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography- see #2 above) can be used to diagnose and treat acute pancreatitis that is caused by choledocholithiasis.

Choleliths on CT Scan

Due to their high calcium salt content, gallstones appear as highly attenuated (very white, like bone) calculi on CT scans. The gallbladder is tucked underneath the liver between the quadrate and right lobes. The image below shows the gallbladder's location as viewed anteriorly.

We must look at the gallbladder in axial cross-section on CT scan, however, so study the image below to get comfortable with the level of the gallbladder in the abdomen. Notice that the gallbladder may be seen next to sections of liver, stomach, pancreas, bowel, kidney, and spleen (a very busy cross-section to study).

The movie file below is the CT scan of cadaver 33487. Move the scan to time 68-70 which is at the L1-L2 level. Try and orient yourself to the liver (H7-H12) and the superior pole of the right kidney (J11). The gallbladder is a low attenuation sac located to the left of the liver (patient's left) and above (anterior to) the kidney. This gallbladder is made easier to see by the presence of a gallstone, visible at time 68-70, J10. Just to the left (patient's left) of the gallstone is the head of the pancreas. Scan just below the gallstone and you will see that areas of the head of the pancreas are also calcified, indicating that this patient possibly suffered from chronic pancreatitis.

The movie file below is the CT scan of cadaver 33515. In this patient we see an example of cholelithiasis that results in the formation of numerous stones. After having practiced on the example above, see if you can find the gallbladder. Scroll down first to find the liver, and then begin searching for a sac near the medial edge of the right hepatic lobe. This patient's gallbladder can be seen from time 62-67 at location G8-H10. Notice at time 65-66, H9.5 you can see numerous calculi in the gallbladder. These are gallstones (cholecystoliths) that have formed and remained in the gallbladder.

The movie below is the CT scan of cadaver 33522. This patient provides an example of cholecystolithiasis resulting in the formation of a single large stone. Begin again by looking for the gallbladder (if you are still having trouble, look at time 68-70, I8-10). Notice the single large calculus at the neck of the gallbladder. With a stone this large in the gallbladder, it is possible that bile was obstructed in its passage from the gallbladder through the cystic duct.

| Copyright© 2000 Thomas R. Gest. Unauthorized use prohibited. |

|

|