|

|

||||||||||||

Dissector Answers - Liver & Gallbladder |

|||||||||||||

Learning Objectives and Explanations:

1. Trace the pathway of bile from the liver and gallbladder to the entry of the bile duct and pancreatic ducts into the 2nd part of the duodenum. (W&B 461, 470-472, N294,N298,N297,TG5-24B,TG5-24C,TG5-26)2. Identify the parts of the liver and gallbladder and describe the relationships of their portal venous, hepatic arterial, and hepatic venous circulation. (W&B 466-468, N287,N289,N300,N302,N312,N289,N291,TG5-19,TG5-21,TG5-22A,TG5-22B,5-28)

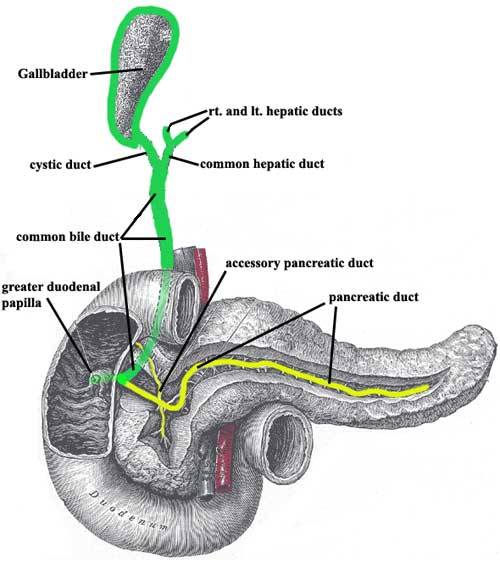

This image is not to scale with regard to the size of the gallbladder relative to the other organs. Connectivity is also not anatomically accurate, but is meant to be illustrative.

Fresh bile from the liver drains out via the right and left hepatic ducts, which join to become the common hepatic duct. Stored bile leaves the gall bladder via the cystic duct. (Please note that bile from the liver also enters the gallbladder via the cystic duct, by traveling retrograde, when the GI tract does not need bile to aid in digestion of food and bile is therefore stored.) The common hepatic duct joins the cystic duct to form the bile duct (often called the common bile duct). (Greek, kystis = bladder, pouch)

The main pancreatic duct begins in the tail of the pancreas and receives tributaries all along its path to the head of the pancreas. Often there is also a separate accessory pancreatic duct (N 298, TG5-26), which drains independently into the duodenum via the lesser (minor) duodenal papilla.

Usually, the main pancreatic joins the bile duct right before entering the duodenum, so they both dump their contents via the greater (major) duodenal papilla (comprised of the hepatopancreatic ampulla, or ampulla of Vater, and the sphincter of Oddi). There is variation in this anatomy, for example, independent dumping of the pancreatic and bile ducts into the duodenum via separate papillae (N N297,TG5-26).

Liver surfaces:3. Identify the structures passing into and out of the porta hepatis and some of the most common variations on this pattern. (N287,N317,N309,N300,N302,N307,TG5-19,TG5-21,TG5-27,TG5-35)Anatomical lobes (see #8 below):

- diaphragmatic: the anterior and superior (and some of the posterior) parts of the liver are in contact with the diaphragm.

- visceral: most of the posterior and inferior surface area contacts abdominal viscera, including the body and pyloric area of the stomach, the superior (1st) part of the duodenum, the lesser omentum, the gallbladder, the right side of the transverse colon (including the right colic (hepatic) flexure), and the right kidney and suprarenal (adrenal) glands.

The gallbladder, IVC, ligamentum teres, ligamentum venosum, and porta hepatis all combine to form an H-shape on the liver's visceral surface (W&B 466, N289,TG5-21). The anatomical lobes can be described with respect to this group of structures:

- right lobe: to the right of the "H"

- left lobe: to the left of the "H"

- quadrate lobe: between the gallbladder and the ligametum teres (the top prongs of the "H") ("quadrate" because it's square)

- caudate lobe: between the IVC and the ligamentum venosum (the bottom prongs of the "H") ("caudate" because it has a tail)

The liver receives arterial blood from the aorta via the celiac trunk, which gives off the common hepatic artery (N300 or TG5-19) as a branch. This artery gives off the proper hepatic artery (N302 or TG5-27), which then divides into the right and left hepatic arteries. Further branching occurs as the arteries supply the hepatic tissue.

The liver also receives the portal vein (N312 or TG5-28), which brings nutrients and other compounds absorbed from the GI tract to be stored and/or processed. Within the liver, the portal vein divides into right and left branches of the portal vein, then further into segmental branches.

The portal venous and hepatic arterial circulation are closely related structurally, with very similar branching patterns within the right lobe. The other lobes have similar branching as well, but are subject to more variation than the right. (The bile ducts also follow this pattern, but of course they are transporting their contents in the other direction.) (N289,N290,N291,TG5-22,TG5-23) This total arrangement is similar in concept to the pulmonary circulation, where the pulmonary arteries, bronchial arteries, and bronchioles have similar branching patterns. Continuing that line of thought, the hepatic veins are similar to the pulmonary veins in that they reside between lobes (segments) and drain blood from two or more adjoining areas.

The gallbladder is a fairly simple sac whose body is suspended from the bed of the gallbladder between the right and quadrate lobes of the liver. Its fundus should reach the costal margin at the 9th costal cartilage. The body of the gallbladder tapers posterosuperiorly to a neck that fills and drains the bile through the cystic duct into the bile duct.

4. Describe the surface anatomy and peritoneal relationships of the liver and gallbladder. (W&B 467-468)The porta hepatis allows passage of the portal vein, hepatic artery, hepatic bile ducts, lymphatic vessels, hepatic nerve plexus (N287 or TG5-27). It is similar to a "hilum", like in the lung or a lymph node. There is also branching of the portal vein and hepatic artery that occurs in the porta hepatis. (N317,N319,TG5-22A,TG5-22B)

As for variations, we are mostly talking about the arterial supply here. In 83% of the cases, the proper hepatic artery arises from the common hepatic artery and branches into right and left hepatic arteries. In 14% of people the right hepatic artery is an independent branch of the SMA and has nothing to do with the common hepatic artery. In 18% of people the left hepatic artery comes from the left gastric artery, either as an accessory to the "normal" left hepatic artery or as the only left hepatic artery. (Note that these situations with the right and left hepatic arteries are not mutually exclusive, which explains why these don't add up to 100%.) Finally, 4% of the time the common hepatic artery is itself a branch of the SMA, but from there the anatomy is "normal". (W&B 475, N300,N302,TG5-25)

When on this topic, we also have to consider the cystic artery, which is a VERY important structure to find during a cholecystectomy. Usually, the cystic artery is a branch of the "normal" right hepatic artery (72%). Of course, if you have one of those 14% where the right hepatic artery comes from the SMA, you would expect the cystic artery to be a branch of that "funky" right hepatic artery (13%). Other uncommon variations include: cystic artery as branch of a normal proper hepatic artery (6%), cystic artery from left hepatic artery, crossing anterior to the bile duct(s) (3%), and cystic artery as an independent branch of the gastroduodenal artery, again crossing anterior to the duct (3%). (W&B 476, N297,TG5-25).

For more than you ever wanted to know about anatomical variation, the University of Iowa has a great site, an "Illustrated Encyclopedia of Human Anatomic Variation". Here is a quick and dirty link to the section on abdominal arteries (including the hepatic arteries).

5. Explain the discrepancy between the external lobulation of the liver and the true internal segmentation of the liver based on the branching of the intrahepatic arteries, veins, and ducts. (W&B 468-469, N289,TG5-23)The liver develops in the ventral mesogastrium, between the stomach and the body wall (check out W&B 441). The connection between the liver and the body wall remains as the falciform ligament (N287,TG5-21) in the adult, while the connection between the liver and the stomach remains as the lesser omentum (N275,TG5-18). The falciform ligament encloses the ligamentum teres hepatis (N229,TG5-21), the remnant of the umbilical vein that brought oxygenated blood from the placenta to the fetal heart. The falciform ligament stretches from the umbilicus to the liver as a double-layered fold. Upon reaching the liver, the layers diverge, with one covering the visceral surface and the other covering the diaphragmatic surface of the liver. (Don't get confused... these are both still visceral peritoneum.) The layer that covers the diaphragmatic surface reflects onto the body wall (and turns into parietal peritoneum) forming the anterior layer of the coronary ligament (W&B 466, Figure 6-40 A). The layers of peritoneum covering the visceral part of the liver also diverge, forming the posterior layer of the coronary ligament (N287,TG5-21). Where these anterior and posterior layers meet are the right and left triangular ligament. (Latin and English combo, falciform = shaped like a scythe or sickle, Latin, teres = round)

The bulk of the liver lies under the right dome of the diaphragm in the right hypochondriac region of the abdomen, with the left lobe extending into the epigastric region. The anteroinferior border of the liver should lie near the right costal margin, with the left lobe being slightly below the costal margin at the infrasternal angle. The fundus of the gallbladder should contact the right costal margin at the 9th costal cartilage and the semilunar line. Disease processes that produce enlargement of the liver will cause its anteroinferior border to project well below the costal margin.

The diaphragmatic surface of the liver rises superiorly on the right to the level of the 8th vertebral level, or the 5th rib, and slopes down slightly to the left, reaching only the left 5th intercostal space.

The anatomical lobes of the liver, which are based on external appearance, differ slightly from the functional (surgical) lobes of the liver, which are based on distribution of the portal vein, hepatic arteries, and hepatic bile ducts. The line of division between left and right is created by the gallbladder and the IVC (one side of the "H" we discussed above). This line divides the liver into right and left portal lobes (older terminology). There is also a third part, the posterior part of the liver, which is the anatomical caudate lobe. It used to be divided into right and left caudate lobes, but now they are combined.

When all is said and done, the liver has 8 functional segments:

posterior part: posterior segment (I)left part:left lateral division:right part:lateral segment (II)left medial division:

lateral anterior segment (III)medial segment (IV)right medial division:anterior medial segment (V)right lateral division:

posterior medial segment (VIII)anterior lateral segment (VI)

posterior lateral segment (VII)Hint: Don't memorize this. Just know that the functional division is different from the anatomical division, and that it is based on blood supply and bile drainage.

Cultural enrichment: Check out these sections from the 1918 version of Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body! Some of the terms are (of course) out-of-date, but the illustrations are timeless.The Liver - The Pancreas - The Portal System of Veins - The Abdominal Aorta - Surface Anatomy of the Abdomen - Surface Markings of the Abdomen

Questions and Answers:

1a. Where are the cystic veins? (N312,N313,TG5-28)2a. What are the fetal functions of the round ligament of the liver (ligamentum teres hepatis, a remnant of the obliterated umbilical vein), and the ligamentum venosum? (N229,TG5-21B,TG5-21C)Small cystic veins pass from the gallbladder into the liver through the bed of the gallbladder. There is an anterior and posterior branch.

3a. Identify the hepatic veins. How many are there? (N265,TG5-34)The round ligament of the liver was the umbilical vein that carried well-oxygenated and nutrient rich blood from the placenta to the fetus. The ligamentum venosum is the fibrous remnant of the fetal ductus venosus that shunted blood from the umbilical vein to the IVC, short-circuiting the liver before birth.

4a. Did you find any hepatic lymph nodes? (N317,TG5-35)Hepatic veins are formed by the union of the central veins of the liver and open into the IVC just inferior to the diaphragm. There are three: left, right and middle hepatic veins.

5a. Review all of the tributaries of the portal vein and completely organize its drainage pattern. What organs does it drain? (N312,TG5-28)The superficial lymphatics can be found in the subperitoneal fibrous capsule of the liver.

6a. Is there any relationship between this intrahepatic pattern and the division of the liver into right and left lobes based on external appearance? (N289,TG5-23)The portal vein collects low oxygen, high nutrient blood from the GI tract and spleen.

See #8 above.